Now you’ve got your theme sorted, the next big task is turning it from the promising start for a book or script into an actual game. And for a game, we need mechanics!

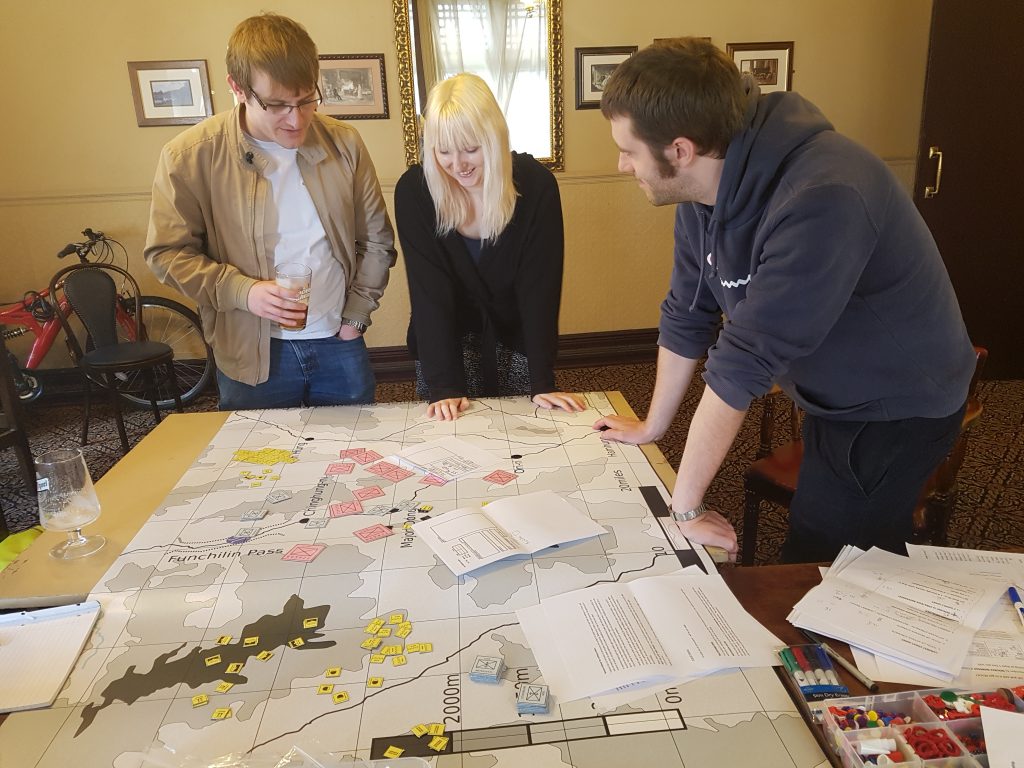

Now as I’m working on Trope High, a very different sort of game, I’ll be missing out a very common set of mechanics at most megagames – the map! But don’t worry if you are hoping to design a game with map mechanics – here’s a blog from Pete about his operational game Case Blue, and I’ll try to circle back to map mechanics at some point too.

But that doesn’t mean Trope doesn’t need a solid base of mechanics! Unfortunately, mechanic design is a MAAAASSIVE topic, and it will be difficult to do it justice in just a single blog post. So here are some pointers that will help you get started creating your own.

My Two Top Tips

- Look at the other games that are out there which are similar to the game you are designing. It’s really hard to create new game mechanics from scratch, but luckily there are tons of ready-made mechanics out there in existing games.

- Find a group to help you test out your mechanics, both for balance and for sanity checking. Are your mechanics fun? Do they make sense? Are they easy to misunderstand, or to break? Existing groups are great, but if you’re nowhere near other megagamers just get a group of friends together.

Creating Mechanics

When coming up with mechanics, it’s important to remember that megagames are supposed to imitate real life – or the reality of the world where the game is set, at least. So consider what the people in the positions of your players would be doing for real.

Within Trope High, I identified the following areas as needing mechanics:

- Lessons, or something to provide students with a GPA and S.A.T. score.

- Extracurriculars, aka the mechanics for both the internal policies within each school club, as well as their measure of success

- Popularity

- Secrets

For your game, the first thing to do is decide what the players will be doing for the majority of the day. If you’re having traditional teams, with set roles within each team, it can be easy to segment players by these role types and create mechanics for them to deal with each turn.

Trope is handling this a little differently, but the underlying idea is the same – players need to have mechanics to structure their turns. Having set phases where players are all doing the same thing helps simplify your game rules and allows players to get into a rhythm.

Phases

In the last blog, I discussed game turns and phases. When you’re coming up with the mechanics is normally the time when you pin down how your turns are going to be divided.

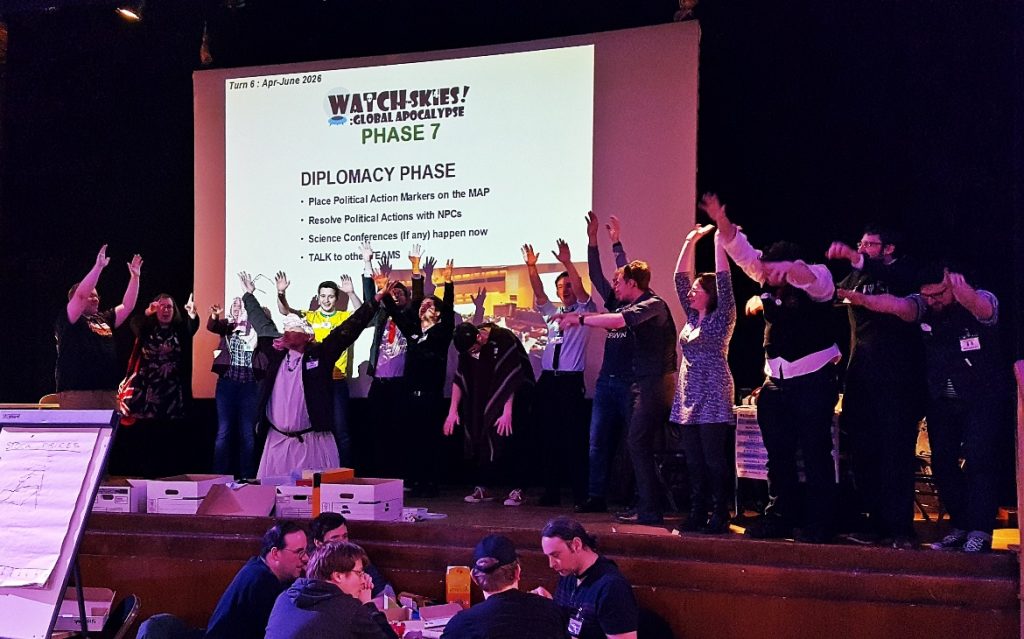

One of the main reason for game delays is having mechanics too complex for the time assigned to them. If you are running 10 minute action turns, but battles can take up to 20 minutes, you are likely to fall behind. This isn’t always a bad thing – if combat players enjoy the long battles, and diplomacy players have plenty to do, feel free to pause the clock – but if other players are going to get antsy about being able to do their next action, consider if you want to cut off actions at a certain time, or length the phases to manage players’ expectations.

Remember that it will always take longer for players to do your mechanics than for you during your tests, because a) they aren’t as familiar as you and b) there are other distractions going on. Be generous with the time you give people to do things.

Currencies

A great way to bring lots of disparate mechanics together is to have them operating on the same currency. For example, in Watch The Skies you can spend in-game money on raising troops, conducting science experiments, trading with other teams, interacting with special cards, and many more activities. A unified currency brings everything together.

Currencies here don’t just refer to money, but to any in-game resource that a player can spend, trade or stockpile. Some currencies may only be accessible to some teams/players, and some may not be tradeable. In-game currencies in megagames have included crew/manpower, rum, cred, military units, ammo, torches, item cards… the list goes on and on.

You can also have multiple currencies in your game. It might make sense to have two different money-types, e.g. one for state-level spending and one for personal spending. Or you might have both money and manpower. Consider also who is receiving the income, and how it will be dispersed through players. If the team lead is holding on to all of it, that can make for a less interesting day for other players.

In Trope, I have two main currencies: Effort chits (which represent the time players have to devote to different activities each turn) and Cred (which represents popularity). Both can be traded, although Cred isn’t on a one-for-one basis, as more popular players can give up less of their Cred to benefit a less popular player with more Cred. Effort expires at the end of each turn, so we’ll be using different coloured chits each turn.

Other things to consider with currency is how much of it you’ll need throughout the day, which we’ll get onto when we talk more in-depth about making and buying game components.

Stats

It’s also useful to consider player stats at this point. Unlike in RPGs, many megagames don’t give players individual stats for when they interact with mechanics, instead creating asymmetrical situations with starting resources, player numbers or in other ways.

But some games do give players or teams their own stats, and I’ll be doing so in Trope High.

It’s important to keep in mind that the human brain isn’t great at remembering numbers. A good rule of thumb is to make sure players don’t need to remember more than 3 numbers. This means there’s benefits to either:

- giving all players the same base stat, and modifying values only for those exceptionally bad or good.

- combining stats together, e.g. making a player’s health the same as their strength.

- using non-numerical stats, such as the colour system above from Pirate Republic.

I am slightly breaking my own rules here, as the current set of Trope mechanics mean each player will have four different stats to remember: Logic, Creativity, Memory and Fitness. Fitness will also incorporate their health tracker. Because I’m breaking this rule, it’s important for me to make it easy for players to check their stats, so I’m likely to include it on their name badges for quick reference.

Trackers

A very common component in many megagames is a public tracker – commonly prestige or panic!

Prestige trackers and the like tend to be very abstract, and adjusted by control’s opinion. These can be useful levers on players, as if they hit the bottom of the prestige track they will be more motivated to do things to move up – and similarly, if they’re at the top, it will often motivate other teams to target them. They very rarely have any in-game mechanical effects.

Meanwhile, panic trackers are usually more mechanised. They’re often a number scale, and Bad Things will happen if you pass certain points on the scale. These tend to have more definitive rules guiding how pieces move up the tracker, although not always.

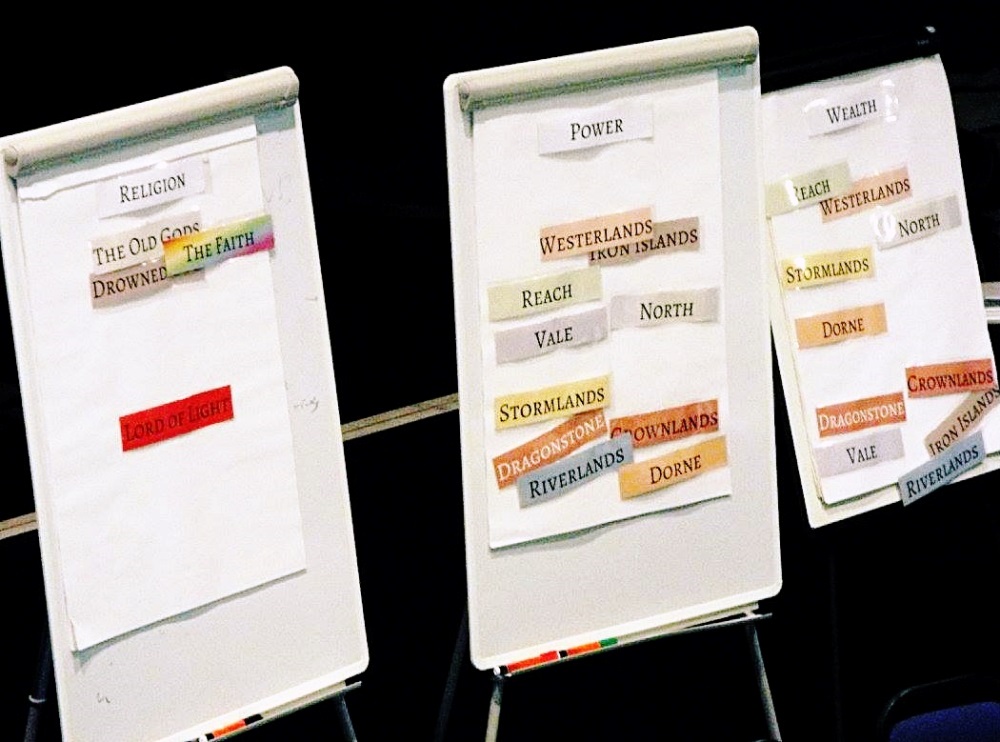

In Everybody Dies, I had five different trackers for Power, Wealth, Honour, Glory and Religion – which was a hell of a lot to keep track of!

In the first game they were ignored completely, in the second I had a specific control whose job it was to keep them up to date, and in the final one I gave it to Assistant Game Control, which was probably the best compromise. But four trackers is too many in my opinion – try to keep it to one or two. In Trope, I’m not featuring any public trackers.

Movement and Communication

Another thing to consider when you’re looking at game mechanics is how strict you’re going to be with movement and communication restrictions. Many megagames, especially modern day or futuristic games, have no restrictions whatsoever, and players can move about, talk to whoever, text, call, pass notes, whatever they feel like.

More historical games tend to have more restrictions, and also games with shorter in-universe turns. If a game turn represents a year, chances are people can talk to anyone within that time period. If it’s a week or a day, that gets less realistic.

Another thing worth bearing in mind is the impact on gameplay and timings. If a player can run off halfway through an action to grab some cash or run something by their team lead, that slows down the game. Many games have restrictions in place governing certain mechanics, such as that players cannot leave the table after an action begins, or councils cannot be disturbed, etc.

In many games where movement or communication restrictions make sense, designers still choose to omit them in favour of better enjoyment by players, or because they know Control will not be able to police them properly. At Trope, comms and movement restrictions don’t really make sense, though I’m likely to restrict it during the Clique phase just for speed.

Creativity

When it comes to actually devising your mechanics… the sky is the limit! There’s a massive trend within megagames at the moment of including more unusual mechanics, rather than dice rolls, card games or counter moving.

Incorporating simple board games and minigames into your megagame is awesome. Jenga is popular for representing unstable situations. Rorschach blots could be a secret code or difficult-to-interpret instructions (or both, as it was at Shot Heard Round The Universe).

Trope is using mechanics as diverse as Coin Football, charades, trivia cards, Connect 4, The Mind and a simplified version of Chrononauts.

Trope Mechanic: Lessons

For Trope, it was also important to remember that this isn’t a high school simulation, it’s a game based on high school tropes. Take academics for example – lessons don’t need to cover real topics and tests don’t need to actually test people. They just need to produce a realistic experience based on the setting, and a realistic outcome for the players.

In high school movies and TV shows, lessons don’t play much of a part. You might have a group of kids studying for a Big Test, or there could be a pop quiz to put people under pressure, or a group project in order to make some unlikely pairings happen, but overall we don’t see much of anyone learning anything.

The two important results are your S.A.T. score, determined ridiculously early in the year tbh, and your final GPA. And this is all about whether you get into a good college or not, and if you get a scholarship.

So rather than make my players sit through agonising hours of lessons when they’d rather be doing something more interesting, I took a very minimalist approach. Lessons cost Effort chits (which must be spent in advance) and then you roll a dice per Effort chit spent (plus one for free each turn). But there’ll be no memorising things or doing sudokus or any of the other ideas I had originally for this.

Keeping the Lesson mechanic simple is also allowing me to be more creative with the extracurricular mechanics, which is likely to be the more interesting part of each player’s day.

Playtesting

The final word on mechanics is – PLAYTEST! Many mechanics have obvious flaws in them that can be sorted by a small amount of testing, but for a lot of designers, the first time their mechanics see the light of day is on game day.

At Everybody Dies, we decided to add in naval battle mechanics about a week before the first game. This was not a good plan – the players picked them apart within minutes, and if it weren’t for a very competent Control on that part of the game, it would have fallen over completely.

Also if you’re playtesting make sure you don’t just test out the teams with the most resources. The first playtest I did for Everybody Dies we practiced battling the Lannisters against the Tyrells – the two teams with the biggest armies! Luckily it was before the game itself that we caught that the discard rules were going to be catastrophic for smaller teams!

Final word on Mechanics

This isn’t the final word. There’s TONS more that can be said about creating mechanics for megagames, and if I have the time I’ll try to add in another post about mechanics later in the series.

But in the mean time – what are your top tips for creating game mechanics? Anything really obvious that I’ve missed?

Others in the “How to Write a Megagame” series

Part 1: Choosing Your Concept

Part 2: Logistics

Part 3: Scoping

Part 4: Mechanics

Part 5: Briefings

Part 6: Secret Plots

Part 7: Casting

Part 8: Teams

Part 9: Control Team (coming soon)